Very pleased to be able to share this new Photobook about my experiences in Bosnia. All profits from the sale of the book will go to the charity Remembering Srebrenica.

21 Bosnia Revisited By DJ Norwood Book Preview

Very pleased to be able to share this new Photobook about my experiences in Bosnia. All profits from the sale of the book will go to the charity Remembering Srebrenica.

21 Bosnia Revisited By DJ Norwood Book Preview

Silhouettes ruling over their kin – Voluminous shadows breaking through the mist, Like abandoned ships cruising a woody sea. In isolation, defining their orbit – Interstellar black holes, consuming light, From a bleached-out sky.

Near immortality lends to the exit door of a church, A spirit more real than any Christian myth. The chapel is orientated around it, Deferring to a power and status as witness, To the folly of civilizations over five millennia.

The connection with eternal life doesn’t end there – Twisted, contorted boughs suggest internal pain, Imprint memento mori of undead beings – Hallucinations of Hydra, Gorgon and Frankenstein, Course through sticky sap like blood, Reddening the bark in winter.

For hundreds of years these knotted fibres defended this Isle, Bending over archers’ backs, straining against sinew, As volley after volley were released at the enemy, Whomever they were, whatever century, For these conflicts are like the gentle breath of summer, Through poisoned, pointed needles.

Images and text © DJNorwood (in isolation) May 2020

7 minute read.

In this second segment of a three-part post I chat with another first-time bookmaker for his behind the scenes experiences of the process.

Kevin Percival‘s quietly insistent work documents the landscapes and communities on the remote Scottish Island of Tanera (Ar Dùthaich), charting the symbiotic relationships left by generations its of inhabitants.

DN: Once again, many thanks for loaning me the book. I’ve had a chance to look through the images and most of the text now. It’s a really beautiful project and object.

It seems like a much more fluid and complicated place when you read the end text than is the case on first viewing. I like the way the book withholds small asides and personal histories until the reader has put in the effort to uncover them…Perhaps that’s for later on in the discussion…

Can I start by asking you your initial motivation for the project and at what point you began to realise it would work best in book form?

KP: I think my motivation was EXACTLY that really: I wanted to make a project which looked at rural issues. Having grown up in the countryside and gradually moved to bigger and bigger towns and cities during my adult life, I gradually became aware of how under-considered and under-represented these rural communities have become in the UK (both politically and culturally). When we consider the rural, we’re so used to seeing these postcard pictures, with blue skies and stunning sunsets- the rural as the ‘sublime’ or ‘picturesque’- all these ideas which have gradually become commercialised and solidified on calendars. To the point where I think we forget that real people still live there, and have to try and carve out an existence for themselves too.

When I first moved there for work in 2012, I didn’t know what shape the work would take – that would develop through making the images. As we drove the final single-track road which snakes from Ullapool out to Achiltibuie where our employers’ boat was moored, we were told that there was a currently a bit of a fuss in the community as petrol at the local stations had recently crashed through the £1.50 a litre mark (at the time this was the same as the premium being paid at motorway service areas on the M25). Given that there was only two buses from Achiltibuie to Ullapool a day- people rely on their own transport (not to mention boats) for work- and this kind of price jump is the sort of difference which forces people to choose between putting fuel in the car or buying food in the most extreme cases. This was the first time I’d really considered this and it really stuck with me throughout the project- though never really makes it explicitly into the work.

We’re bombarded by stories about inner-city poverty all the time, but rarely even consider what people in the countryside do. I was once told by an ecologist friend a story of her going into a city primary school. She asked the pupils she was teaching “Where does milk come from?” and was told “from a bottle”. When she asked where it comes from before that – kids tentatively said “milk comes from Tesco”. This is just one example of how urban and rural realities do not intersect. So all these ideas were floating around in my head as I made the work. I didn’t want to deny beauty of the area, because ultimately I’ve always been fascinated by the ecology and Romanticism of the countryside, but I wanted to balance that by saying ‘hey, people make their lives here too it’s more than just a chocolate box’. Putting the work into a book allowed me to blend these narratives together in a more complex way. The idea was to make a book that rewards repeated viewings, so each of the oral histories you read, gives you a very slightly different sense of the place and understanding of the photographs.

The images are made up of portraits, vistas and details the exception being a couple of interiors. In relation to the portraits, did you have a specific cross-section of the community you wanted to represent as a kind of ethnographic survey of the island? How did you go about selecting your subjects?

For the portraits, I tried to show anyone I met whose work or lives impacted on the island at the time we were working there. There were only 5 people living on the island including us, so I focussed on people who lived on the mainland but influenced the daily running of the island.

I often talk about my interest in the traces found in the landscape- the evidence of human interaction with it and presence upon it. I wanted to show the people leaving those traces now in the early 21st century.

My only regret here is not showing more of the holiday makers who often visited every single year for periods of 10 or 15 years. I tried to show a mix of people from different backgrounds and ages though.

When it came to doing oral histories, I felt it was particularly important to represent a variety of perspectives- from young people right through to those in their 60s/70s. From people who have moved to the local area relatively recently, to people who have lived there all their lives- be that 18 years or 60.

It seems to me that one of the most rewarding aspects of bookmaking is the editing – making new relationships with the image so connections are made visually where none existed before – but also the most fraught in the sense that this is a very definite process and once it’s done there’s no going back. You are, in a sense, creating a finalized world in which to immerse your viewer…

In terms of editing that was a really, really long process and I think it’s a really ‘how long is a piece of string’ question – it really varies from project to project and person to person. Almost from the beginning I was working on a rough edit. After our first summer on the island in 2012 I’d scanned and worked on a selection of images- probably about 50 or so that I was interested in, and this informed my shooting for the following year, which meant it became much more directed. I made another edit in 2013 and some of the gaps had been filled in, but others became obvious. So I continued to go back and shoot, editing between trips.

I made my first dummy book around this time, 2013/2014 when I started my MA. I wasn’t too happy with it so left off trying to get the book into a final form for 2 years or so to work on other projects. It wasn’t until early 2016 that went back and I really began to feel like I was getting somewhere. I find editing an uncomfortable process. With this project, it’s when I realised just how attached I’d become to the actual place – never mind the images. It’s very easy to establish relationships with certain images and over time those relationships can easily become entrenched- particularly when working on something for so long. I think you eventually get to a point where you have no idea what’s ‘good’ any more!

I feel very fortunate that I had a bunch of amazing photographer friends who I’d met in various places and I had a lot of help from them, firstly cutting the numbers down to a manageable level, and then bouncing ideas around for the final 66 images which made it into the book. It’s fascinating to see what other people find interesting in your images. I have no problem with handing someone I trust a handful of ordered prints I’ve agonised over for days, and saying ‘make an edit’, watching as they undo all your hard work! Call me a masochist but it’s all part of the process – it quickly brings your own objectivity back if you can let go a bit.

The people I edit with also ask the hard questions – if there’s an image they’re not sure on- you need to be able to justify why it’s there. They don’t have any of your emotional attachment to the particular situations you remember whilst you were photographing.

In the final 6 months before printing, the sequence was re-edited I don’t know how many times, and I had people from wildly different areas, fashion photographers, documentary photographers, commercial. I prefer to work with prints, little contact prints 6x6cm mostly, followed by about 12x12cm once the edit is down.

I felt so ready to get the project out by this point so the editing wasn’t fraught in that sense, but I was very conscious I wanted to do the land and the people justice. Like many things, it’s a deceptively simple story, which belies a hugely layered, complex ecology of place and I really wanted to get some of the complexity across. So that’s where the pressure comes- am I being honest? Am I exploring the many truths of the place and the people? Am I telling these stories fully and with sensitivity?

Due to funding through KickStarter my time-frame for production was super short- print/design was all done within about 3 months. Sean, my designer absolutely took me under his wing at this point, having done a few photobooks of his own (check out his work seandooley.com). He made some helpful final sequencing tweaks, worked up the designs quickly and gave it a much cleaner, more ‘modern-yet-classic’ look than I had in my dummies. I went round getting quotes from a bunch of printers but ended up going with one in Italy who Sean had used before.

My biggest lesson learned here was to always go out [to the printers] and be on press for the printing. In the end I didn’t have the money to do this, but I think it would have smoothed out a bunch of communication issues. Proofing long-distance is a ball-ache. I was really pleased with the final print quality, but getting to that point via email was mainly due to the fact that the printer was so experienced.

Also, no matter how much time you build in to the schedule (seriously- even if it’s months..) I would NEVER again book a launch before the books have come off the press.. If doing a small one-off print-run your baby will get bumped down the print queue if a bigger job comes in. And that’s before deliveries get delayed at customs/for bad weather/because of aliens/strikes/badgers etc.

Ha! The image of militant badgers picketing outside post offices is a strong one. Thanks again for your time and I wish you every success with the book. Buy it here.

All images ©kevinPercival

4 minute read

In a this three-parter, I interview photographers venturing out for the first time into the sometimes intimidating world of book publishing. Each has their own take on the process, and speak with refreshing candour about their experiences.

First up, my former boss and gifted photographer Steve Meyler. His latest project, 66 hours, employs the landscape as metaphor to talk about a tragic episode in the history of a coastal community. You can read all about the project here.

DN: Hi Steve! I thought I’d share some ramblings from folk about book making and I wondered if you would like to contribute. Hope so. Do you have any pithy tips for aspiring newbies in the wonderful world of publishing? Love to hear your thoughts…

SM: Here we go – my two penneth – just rattled this out for you, whilst sitting in the sun (summer 2019!ed) and enjoying the sea breeze…

First, decide what your aspirations are.

Do you want to be the next Stephen Shore, or are you happy to publish for friends and family? Without being a terrible pessimist, the world is full of amazingly talented snappers generating fantastic work, it’s unlikely most ‘smudgers’ that self-publish books are going to end up with the world at their feet.

What’s your aim when producing a book?

The best, purest and most noble reason to create a book or zine is to produce an object; as beautiful an object as possible, to share with others. As photographers, we tend to focus our attention primarily on content but it is perhaps wise to remember you’re also creating and presenting/selling an object. Would you tote your best work to and from galleries in the worlds cheapest portfolio case? – probably not! I’m still very much a newb to this world myself and squarely fall into the category of publishing books in small runs for a local or friend oriented customer base.

Where does cost fit into the overall scheme?

My only goal is that the projects pay for themselves if there’s a small profit, that gets funnelled to the next piece. If there was to be a loss, then I would do my best ensure it wasn’t a big one. This leads to the first golden rule derived from my experience – don’t order too many books from the printer. There are printers out there that specialise in small runs of self-published work and will produce as few as 50 copies at a time. These are digitally printed works (more on this later).

In your experience, can you describe the technical aspects of the printing process?

So, if you have a huge market to service and require a minimum of 500 books then Offset printing is the way to go. Superb quality from carefully made printing plates that are yours to keep, which, if there’s a mistake (typos etc.) are there forever. The cost per copy is very low in high volume. For B&W with high contrast and deep rich blacks, duotone is the recommended process.

For small runs of books which can be corrected from run to run, the digital press is the answer. In recent years digital presses have come on in leaps and bounds and a good printer will produce images (particularly in colour) that rival an offset press. For high-quality B&W on digital, I would advise using a 4 colour process to create what a printer calls ‘rich black’. The alternative is a ‘flat black’, this is the preferred option when cost is the primary concern or the depth of black in your images is not a concern. Paper choice is, of course, a personal matter but for photographers, the opacity of the paper is Important, ‘bleed through’ from the previous page is undesirable.

Where would you suggest people start with the design of their books?

I would suggest using a professional designer unless the work overall is lo-fi or very simple indeed. Photographers get rightly annoyed when they hear about amateurs taking work away from them and producing sub-standard work, the same goes for book design – pay a professional, it’s worth the money.

So you have your run of beautifully designed and realised books, can you talk us through your approach to marketing?

The final part of this mini business is of course pricing. If you’ve been snapped up by Faber & Faber for a 20 book deal, you don’t have to worry about the next bit. If you’re self-publishing in low volume, however, It’s a very simple retail business price segmentation. If a copy of your book has cost you £20 to produce, then a standard profit margin would be a further £20 for the author, bringing your wholesale price to £40. Any retailer or onward seller will then want the same margin leaving your RRP in a bookstore at £60. This final pricing segment can be mitigated if you sell in person but it’s easy to forget the additional costs of running your mini-publishing house, a website or money handling fees are examples. When it comes to shipping, the cost, of course, varies with location and this has to accounted for in your production costs and profit margins. The best way to ship photobooks and ensure they arrive in perfect condition is to use an oversize cardboard padded bag. Wrap the book in plenty of small bubble wrap, ensure it fits tightly into the bag and the package will survive any manner of abuse. The packaging cost will obviously be commensurate to the quality and cost of the contents.

Thanks Steve! Do you have any final words of wisdom to share..?

Remember a book is a long term investment, don’t be too discouraged if initial sales are slow. Your creation will be for sale as long as you have stock and its gratifying to know that people will part with their hard earned cash to own your work and keep it in their home.

66 hours is now sold out, but Steve has some fine prints for sale in his online store, as well as other contemplative and provocative projects that deserve time and reward scrutiny.

All images ©Steve Meyler

5 minute read.

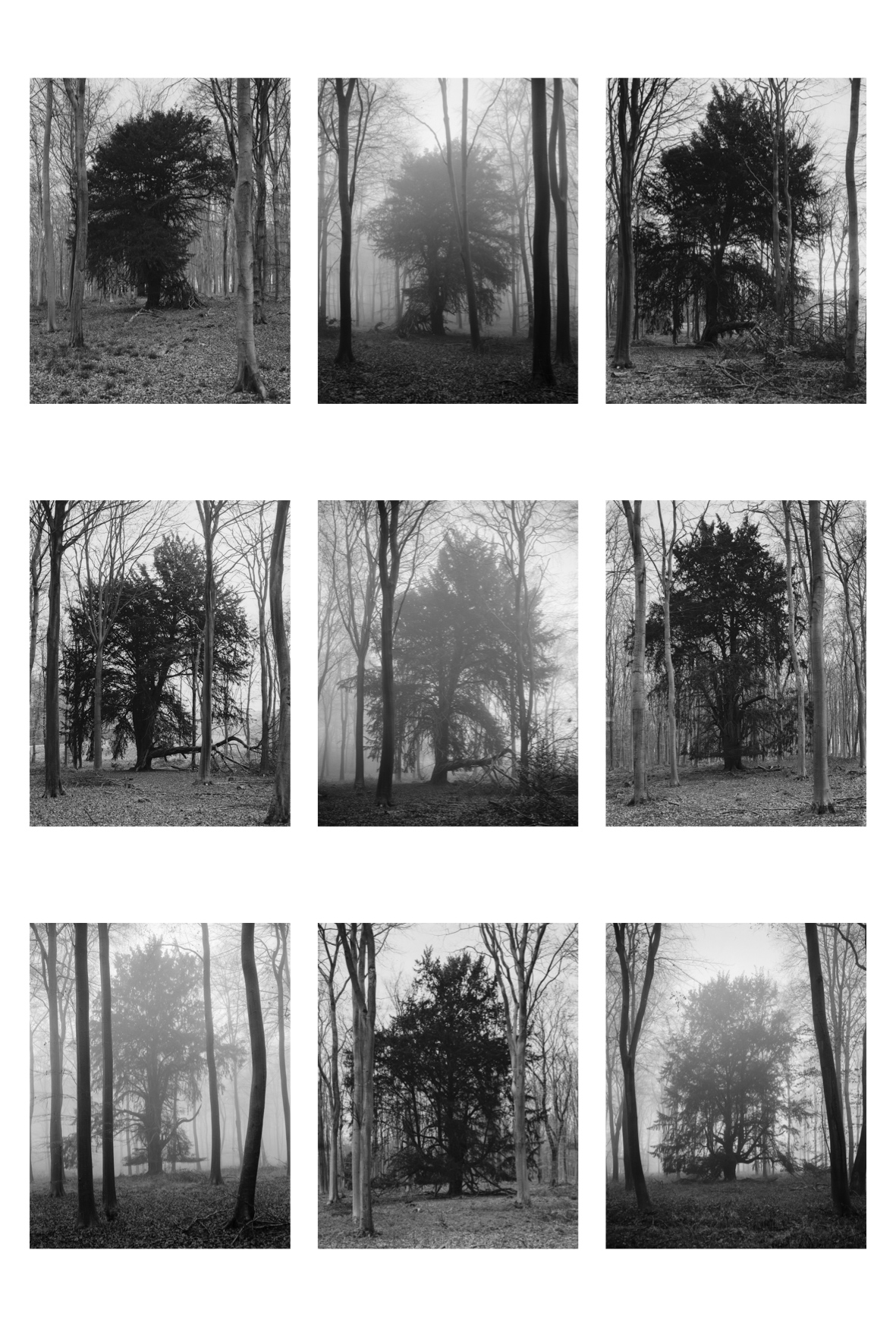

Pictures in honour of the extinction rebels.

The following is an extract from influential human geographer Yi-Fu Tuan referencing mythology and environmentalism.

‘In the Chinese cosmological order, things that belong to the same class affect each other. The process, however, is not one of mechanical causation but rather one of “resonance.” For example, the categories east, wood, green, wind and spring are associated with each other. Change one phenomenon – green, say – and all the others will be affected in a process like a multiple echo.

‘So the emperor has to wear the colour green in the spring; if he does not the seasonal regularity may be upset. The idea here stresses how human behaviour can influence nature, but the converse is also believed to occur. Nature affects man: for example, “when the yin force in nature is on the ascendancy, the yin in man rises also, and passive, negative, and destructive behaviour can be expected.”

‘Environmental influence is clearly recognised in the cosmological order of the Saulteaux Indians. Thus the winds are not the only powers in nature that have to be classified and located in space, they are also active forces in conflict over the middle ground where man lives.

‘North wind declares that he intends to show no mercy to humans; South Wind, in contrast, intends to treat humans well. The fact that North Wind cannot defeat South Wind in battle means that summer will always return.’

Mythical Space and Place, Yi-Fu Tuan

Pictures made in woods north of Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire threatened with destruction by the HS2 Project.

All images ©djnorwood 2015

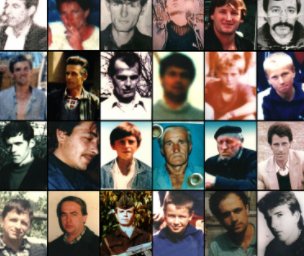

Context: On 11th July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces, led by General Ratko Mladic, systematically massacred 8,372 men and boys. It was the greatest atrocity on European soil since the Second World War. The International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia ruled that the mass executions constituted genocide.

We visit the Potocari war graves and see for ourselves the names of the dead, carved into granite. In alphabetical order the obliteration seems even more acute. The names of the deceased are etched into recumbent flagstones as if even this, the most durable of materials, finds it hard to bare its mute tirade.

Skeletal remains retrieved from mass graves line the walls of an ordinary building on the outskirts of Tuzla. Sometimes these body fragments are found in different sites, many miles apart. How so? In some cases dug up and moved to the frontline. All the better to suggest death in the virtuous of acts of bi-partisan combat rather than the miserable, one-sided slaughter which befell so many.

Contemplating this landscape with all its secrecy and obfuscation, small details suddenly coalesce into something tangible. Concrete pipes line up as if on parade. PVC doors, confined to a lot, dream of the short journey to the nearest half-finished home. Farmers re-attach fallen vines with pliers and wire. Men and women appear like statues, immobile yet fragile, while the world spins, the sun blinds and the real becomes elusive and ephemeral once more.

A proposal…

© djnorwood 2019

‘That image reminds me of something. It ignites a small flame that lights my way through the filing system of my mind. It brings me eventually to the hint of a memory, and that memory guides my interpretation of the image, influences my reaction, connects my thoughts and feelings, and threads them together, binding them into a new collection, to be drawn upon the next time something familiar arises.’ – Karen Harvey

© djnorwood 2019

The series is taken from a body of work exploring a derelict house and garden in a rural English community. These pictures document apple trees over a period of two seasons during which time the house was bought, sold and bought again. The new owner is slowly clearing the site and dismantling the outbuildings in preparation for a new home in its place.

© djnorwood 2019

As with any house, small details of previous occupants remain. In this case, the outbuildings sprung up organically over time, encompassing a workshop, poultry coups and pigeon lofts. Evidence of this industry is everywhere, including newspaper cuttings from the 1930’s plastered on a wall dating from when the house was originally built.

© djnorwood 2019

In Christian tradition the apple is a symbol of knowledge, temptation and desire. Recently, it has come to symbolise design, technology and corporate power. As time passes, knowledge accumulates, is gathered, is consumed, or alternatively, it settles in forgotten seams, ready to be re-discovered. As with all things, it deteriorates and is subsumed into something else.

This is everything I ever learnt.

© djnorwood 2019

© djnorwood 2019

‘The city, in its Victorian overcoat, the muck of centuries on its waistcoat, bored Ballard. He promoted this new place, the rim. The ‘local’ was finished as a concept. Go with the drift, with detachment. The watcher on the balcony. Areas around airports were ecumenical. They were the same everywhere: storage units, hangars, satellite hotels, car hire companies, apologetic farmland as a mop-up apron for Concorde disasters.’

– Iain Sinclair, London Orbital

900 words –

‘Bastard Countryside’, the new book by photographer Robin Friend takes us on a tour of the so called ‘edgelands’ of the UK, pointing out the beauty, mystery and sublime in these 21st century backwaters. In a small autobiographical passage in the front of the book, Friend acknowledging that we still live in a world largely defined by the socio-economic constraints of the past, especially in terms of land ownership and use. Yet this is much more than a dry survey of the rural landscape. It is an archaeological adventure both impressively expansive and movingly intimate. A metaphorical quest of self-discovery as much as a survey of a bruised and battered Britain.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

The pictures aren’t rooted to any specific geographical locale, either by topographic reference or text. Instead, they seem gloriously unhinged, able to float free of worldly constraints to instead occupy a space that hints at a greater resonance between the image and the unconscious.

Friend’s enigmatic approach could be seen as adding to the mis-firing cannon of so-called ‘edgeland fetish’ as identified by the writer Robert MacFarlane, who provides the lucid afterword. Yet this malediction is confronted by one image in particular – the forelorn carcass of a stranded whale – its blood still leaching into the surrounding sea. This is the factual pivot around which the rest of the work’s fictional narrative seems to balance, tipping the argument away from delusions of the pastoral towards something altogether darker, more political and relevant. Like an embedded harpoon unleashed from the decks of the Pequod, Captain Ahab’s ship in Moby Dick, this image becomes engrained in us, adding poignancy and, paradoxically, life to the book as a whole.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

On this exploration we’re encouraged to meditate on the possibility and meaning of what we find. Friend’s photographic style shuns the cool formality usually associated with historic schools of landscape photography, instead drawing us in with a sophisticated palette of muted tones, interspersed with discordant notes of red and blue as nature’s harmony is rudely disrupted.

Elsewhere, and bearing in mind that, on the face of it, this is an interogation of ‘the countryside’, the archetypal ‘verdant hills’ of a ‘green and pleasant land’ are resolutely absent and draw attention to the artificiality of such terms. In fact, the conspicuous omission of the predominant colour of nature is one of the over-riding impressions here. Where green does feature, it becomes as man-made as a paved driveway – a gangrenous graft of grass or a slimy slither of sea-weed that, like a contaminated limb, seems to hinder rather than help us on our way. Or, verging on the darkly comical, it becomes something to be burnt.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

Like the Victor Hugo novel Les Miserable from which the title of this book is derived, this publication is a blend of drama on the micro and macro scale. Large format images repleat with the significance of unfolding narratives interlink with more prosaic digressions that nevertheless take on a sense of the epic, treated as they are with the same meticulous attention to detail. For example, a rusted tin can hidden in a hedge leads seemlessly on to a hulking shipwreck ravaged by tide and time. One gets a sense of the editing here, and the significance of pace, flow and cohesion. The result is a paired-back approach that expertly choreographs form and content into an articulate whole.

The remains of an array of human endevour are exposed to the lens, notably traces from the industrial revolution and the second world war. Many of these spaces and objects are tantalisingly familiar and have contemporary concerns. The recycling facility sorting material into its debased state; the wind farm blighting the bucolic view; ‘an abandoned greenhouse gradually re-mossed,’ as identified by Macfarlane. In less skilful hands these images could have easily tipped into cliché, but not here.

A sequence of penultimate pictures delve into the subterranean world of the tunnel, sewer and cave, reinforcing not only a sense of journey and adventure, but also of apotheosis – the idea of consumerist culture reaching a kind of zenith. Peak stuff, in the literal and metaphorical sense has never been so plainly or keenly observed as here in the blocked bowels of the earth.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

Friend seems to be echoing, in these underground caverns, the words of the photographer Robert Adams who says, ‘the area’s ruin would be a testament to a bargain we had tried to strike. The pictures record what we purchased, what we paid, and what we could not buy. They document a separation from ourselves and, in turn, from the natural world that we professed to love.’ The bargain in ‘Bastard Countryside’ seems to be at the expense, not only of the surface of the land, but the very internal workings of the earth itself.

Yet truisms crudely articulated render the poetics of art redundant. Here there is beauty (this ugly word) in the most maligned of places – a gift the photographer has captured and translated into form. The possibility of hope that, in time, we might seek to alter our ways and find an alternative to this malaise. What is pictured here is the aftermath of violence, the chaotic clash between global capitalism and nature, played out in a poet’s back yard.

Bastard Countryside by Robin Friend, published by Loose Joints through to www.loosejoints.biz

Tend /tend/ v. 1. tr. care for, take care of, look after, look out for, watch over, mind, attend to, see to, keep an eye on, cater for, minister to, nurse, nurture, cherish, protect.

‘Free from market obsessions of scarcity, hunters’ economic propensities may be more consistently predicated on abundance than our own.’

Marshall Sahlin, in his essay ‘The Original Affluent Society, from his book ‘Stone Age Economics’.

An allotment after its allotted time. Eyed at by prospectors intent on converting to cash. Onions, potatoes, radishes, carrots and leeks vie with burdock and bramble for a stake (literally) in the remains of the fertile ground.

These are the forgotten remains of careful conservation and cared for cabbages. Beneath the foliage of strange and unfamiliar plants, whose fronds sway elegantly in the dusk’s last breath, rutted earth dug in right angled rows turns the ankle of unsuspecting trespassers. Stumbling, legs follow eyes reluctantly to the next abandoned, skeletal shed.

I wandered down one summer evening when the upward heat from the earth met the low sun’s last residual rays. I heard the percussive notes of shattering greenhouse glass: a whisper of boys huddled around an air- rifle, taking aim at anything that caught their eye. I wondered whether I should go down and try to negotiate a picture, but thought better of it. I didn’t doubt my own safety but knew those moments with mates – when some random stranger crashes a summer evening – were times that shouldn’t be interrupted. The suffocating heat was a warning that this was a place where I had no legitimate walk on part.

I waited at a distance. After seeing them burn up and out of the estate, I eased into the tall grass – a similar sensory experience to wild swimming such was the feeling of immersion. I lost a few skin cells to the tips of brambles wading between islands of 2by4 and fetid felt. A few surprising things were left behind: a tool kit never used, still in its box (with receipt); a variety of manual tools in states of distortion – gappy forks with missing tangs; bundles of brittle bamboo gathering dust; garden sieves that reminded me of a recurring childhood dream of panning for gold in the Klondike (aka the seasonal stream at the bottom of the garden).

The sense of industry in this place is palpable. Animal, insect and plant vie with the human to create layers of elaborate existential references. Small pathways or ‘smouts’ in the tall grasses elude to the nocturnal commute of rodents and small mammals. A beautifully formed abandoned wasps nest suggests ours is not the only reality – that there are other worlds living with us, in parallel but not linear time. A micro cosmos, yes, but no less beautiful and arguably more relevant than its celestial cousin.

So, when the bulldozers move into this vacant lot, another ‘unproductive’ space will be won over by the money men. The direction of travel here is unsurprising. A frictionless future perhaps, but one which marginalises the already under-appreciated moments and significance of and in this abandoned place.

I’ve been returning (when I can) to a practically invisible agricultural feature in the landscape. ‘Pits (dis)’ are extraordinary in their prominence on local OS maps – I’ve noted, astonishingly, ten of these things in one square mile close to home. They are evidence of the excavation of chalk used to apply as fetilizer to fields and as an acidity regulator before modern farming practices made this process redundant. Quite often they feature as strange wooded outcrops in the middle of ploughed fields, especially noticable in winter.

I decided to return to this particular one (OS ref: 465 528) repeatedly over a period of two years documenting seasonal and climatic change from one viewpoint.