‘The city, in its Victorian overcoat, the muck of centuries on its waistcoat, bored Ballard. He promoted this new place, the rim. The ‘local’ was finished as a concept. Go with the drift, with detachment. The watcher on the balcony. Areas around airports were ecumenical. They were the same everywhere: storage units, hangars, satellite hotels, car hire companies, apologetic farmland as a mop-up apron for Concorde disasters.’

– Iain Sinclair, London Orbital

900 words –

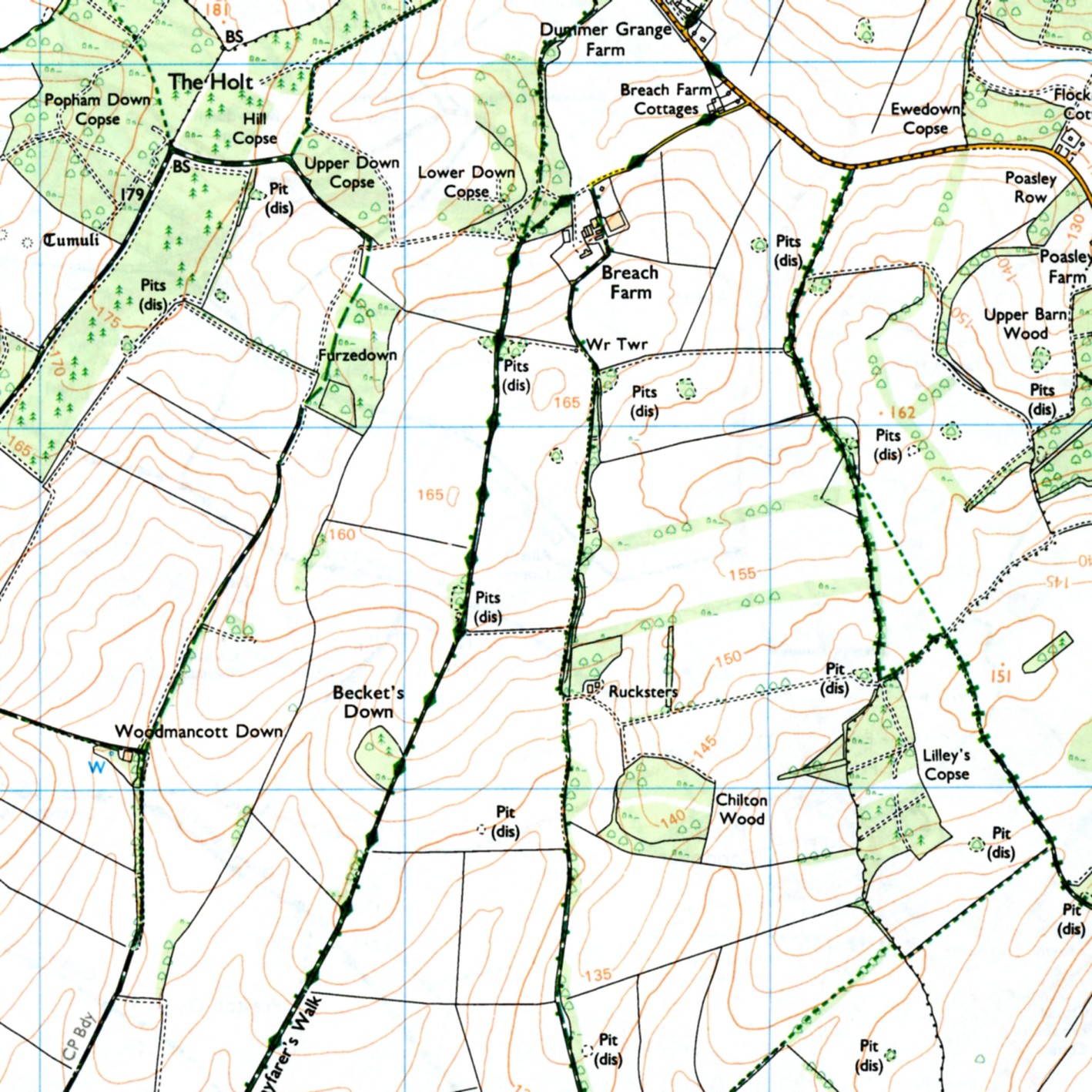

‘Bastard Countryside’, the new book by photographer Robin Friend takes us on a tour of the so called ‘edgelands’ of the UK, pointing out the beauty, mystery and sublime in these 21st century backwaters. In a small autobiographical passage in the front of the book, Friend acknowledging that we still live in a world largely defined by the socio-economic constraints of the past, especially in terms of land ownership and use. Yet this is much more than a dry survey of the rural landscape. It is an archaeological adventure both impressively expansive and movingly intimate. A metaphorical quest of self-discovery as much as a survey of a bruised and battered Britain.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

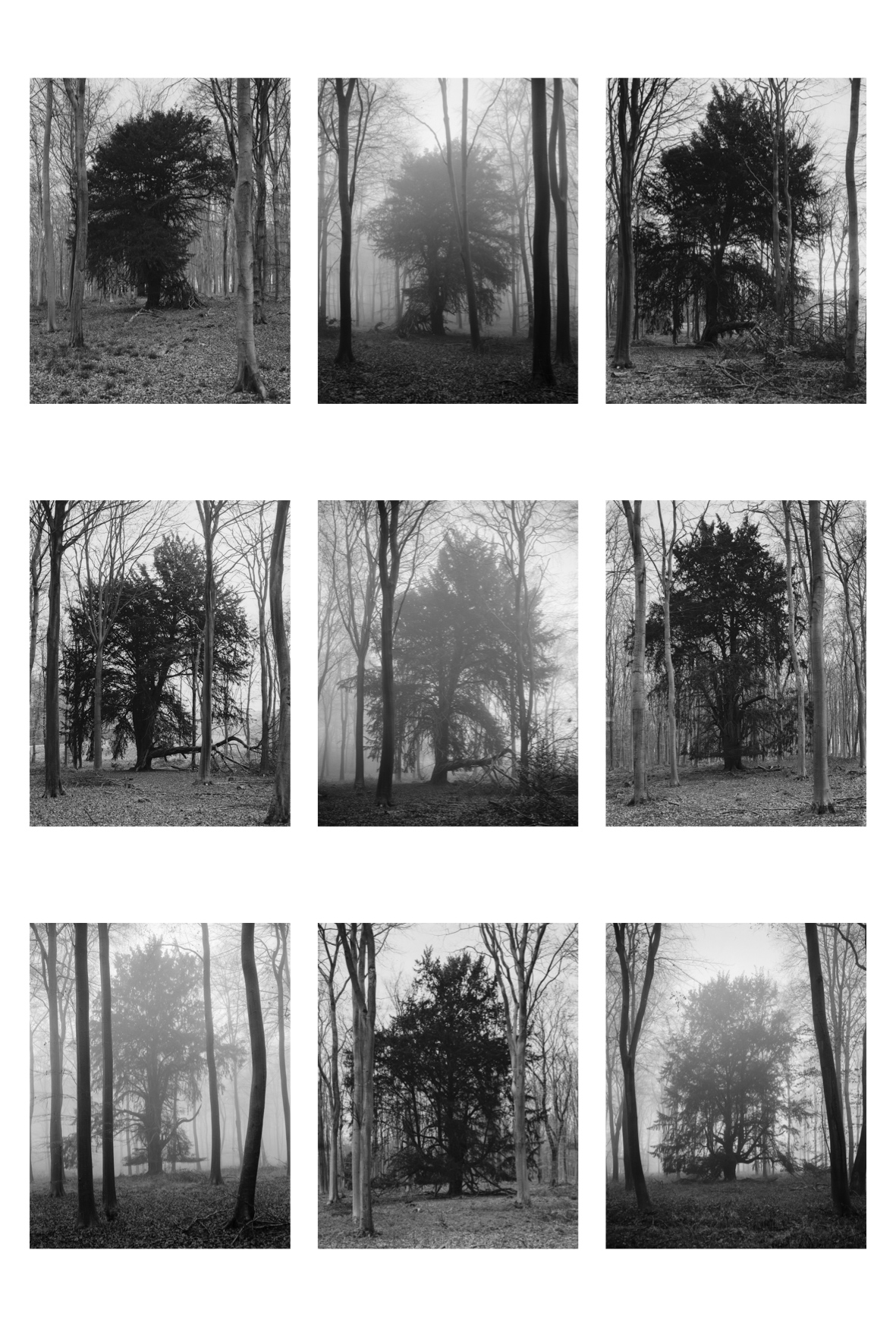

The pictures aren’t rooted to any specific geographical locale, either by topographic reference or text. Instead, they seem gloriously unhinged, able to float free of worldly constraints to instead occupy a space that hints at a greater resonance between the image and the unconscious.

Friend’s enigmatic approach could be seen as adding to the mis-firing cannon of so-called ‘edgeland fetish’ as identified by the writer Robert MacFarlane, who provides the lucid afterword. Yet this malediction is confronted by one image in particular – the forelorn carcass of a stranded whale – its blood still leaching into the surrounding sea. This is the factual pivot around which the rest of the work’s fictional narrative seems to balance, tipping the argument away from delusions of the pastoral towards something altogether darker, more political and relevant. Like an embedded harpoon unleashed from the decks of the Pequod, Captain Ahab’s ship in Moby Dick, this image becomes engrained in us, adding poignancy and, paradoxically, life to the book as a whole.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

On this exploration we’re encouraged to meditate on the possibility and meaning of what we find. Friend’s photographic style shuns the cool formality usually associated with historic schools of landscape photography, instead drawing us in with a sophisticated palette of muted tones, interspersed with discordant notes of red and blue as nature’s harmony is rudely disrupted.

Elsewhere, and bearing in mind that, on the face of it, this is an interogation of ‘the countryside’, the archetypal ‘verdant hills’ of a ‘green and pleasant land’ are resolutely absent and draw attention to the artificiality of such terms. In fact, the conspicuous omission of the predominant colour of nature is one of the over-riding impressions here. Where green does feature, it becomes as man-made as a paved driveway – a gangrenous graft of grass or a slimy slither of sea-weed that, like a contaminated limb, seems to hinder rather than help us on our way. Or, verging on the darkly comical, it becomes something to be burnt.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

Like the Victor Hugo novel Les Miserable from which the title of this book is derived, this publication is a blend of drama on the micro and macro scale. Large format images repleat with the significance of unfolding narratives interlink with more prosaic digressions that nevertheless take on a sense of the epic, treated as they are with the same meticulous attention to detail. For example, a rusted tin can hidden in a hedge leads seemlessly on to a hulking shipwreck ravaged by tide and time. One gets a sense of the editing here, and the significance of pace, flow and cohesion. The result is a paired-back approach that expertly choreographs form and content into an articulate whole.

The remains of an array of human endevour are exposed to the lens, notably traces from the industrial revolution and the second world war. Many of these spaces and objects are tantalisingly familiar and have contemporary concerns. The recycling facility sorting material into its debased state; the wind farm blighting the bucolic view; ‘an abandoned greenhouse gradually re-mossed,’ as identified by Macfarlane. In less skilful hands these images could have easily tipped into cliché, but not here.

A sequence of penultimate pictures delve into the subterranean world of the tunnel, sewer and cave, reinforcing not only a sense of journey and adventure, but also of apotheosis – the idea of consumerist culture reaching a kind of zenith. Peak stuff, in the literal and metaphorical sense has never been so plainly or keenly observed as here in the blocked bowels of the earth.

© Robin Friend 2018 courtesy Loose Joints

Friend seems to be echoing, in these underground caverns, the words of the photographer Robert Adams who says, ‘the area’s ruin would be a testament to a bargain we had tried to strike. The pictures record what we purchased, what we paid, and what we could not buy. They document a separation from ourselves and, in turn, from the natural world that we professed to love.’ The bargain in ‘Bastard Countryside’ seems to be at the expense, not only of the surface of the land, but the very internal workings of the earth itself.

Yet truisms crudely articulated render the poetics of art redundant. Here there is beauty (this ugly word) in the most maligned of places – a gift the photographer has captured and translated into form. The possibility of hope that, in time, we might seek to alter our ways and find an alternative to this malaise. What is pictured here is the aftermath of violence, the chaotic clash between global capitalism and nature, played out in a poet’s back yard.

Bastard Countryside by Robin Friend, published by Loose Joints through to www.loosejoints.biz