Pits. Everywhere, pits.

©Crown Copyright 2015

The dimpled remains of an agricultural past litter the landscape. Farm labourers gathered its chalky alkaline nutrients, then applied it back to the topsoil as fertilizer around a hundred years ago. Then, fields were smaller and could be re-energized more easily with modest machines and brute strength. Pastures were dotted with people, talking, shouting, singing even.

Go to a ‘less advanced’ nation, Morocco say, and listen to the sounds the land encourages people to make. Whooping in the cold morning light. Toiling ‘till the sweat appears. I’ve been there and heard it. I’ve camped out under the stars on a rocky hill by the side of the road: pitched up by bicycle the day before, thinking I was the only one for miles. As dawn broke, a work party lying low nearby filled the air with the clatter of their pick-axes, which reverberated round the valley walls. These were the sounds that once resonated in the spaces carved out between these woods, in these pits. Now this clamour of voices is consigned to the past.

Al Haouz, Morocco ©djnorwood 2015

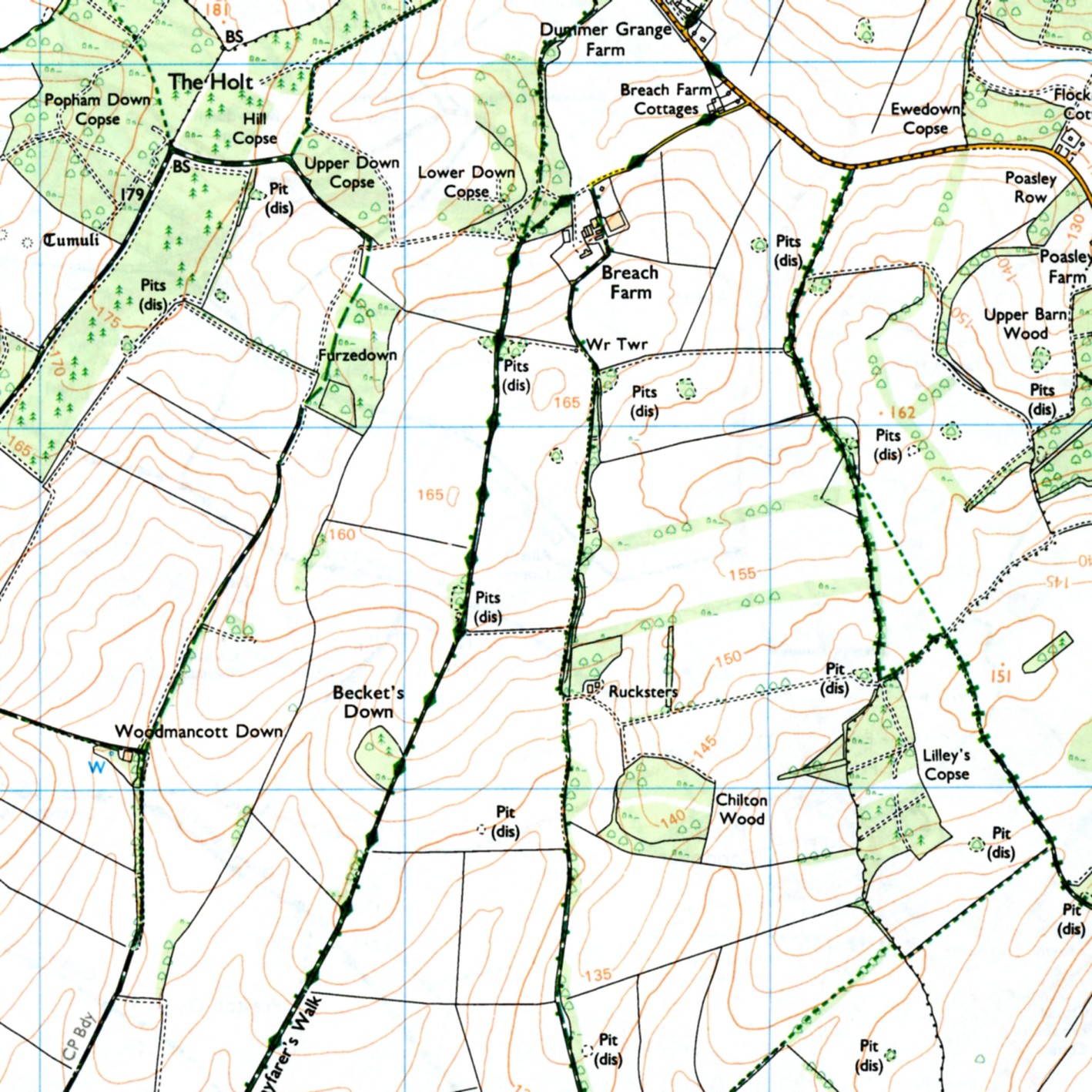

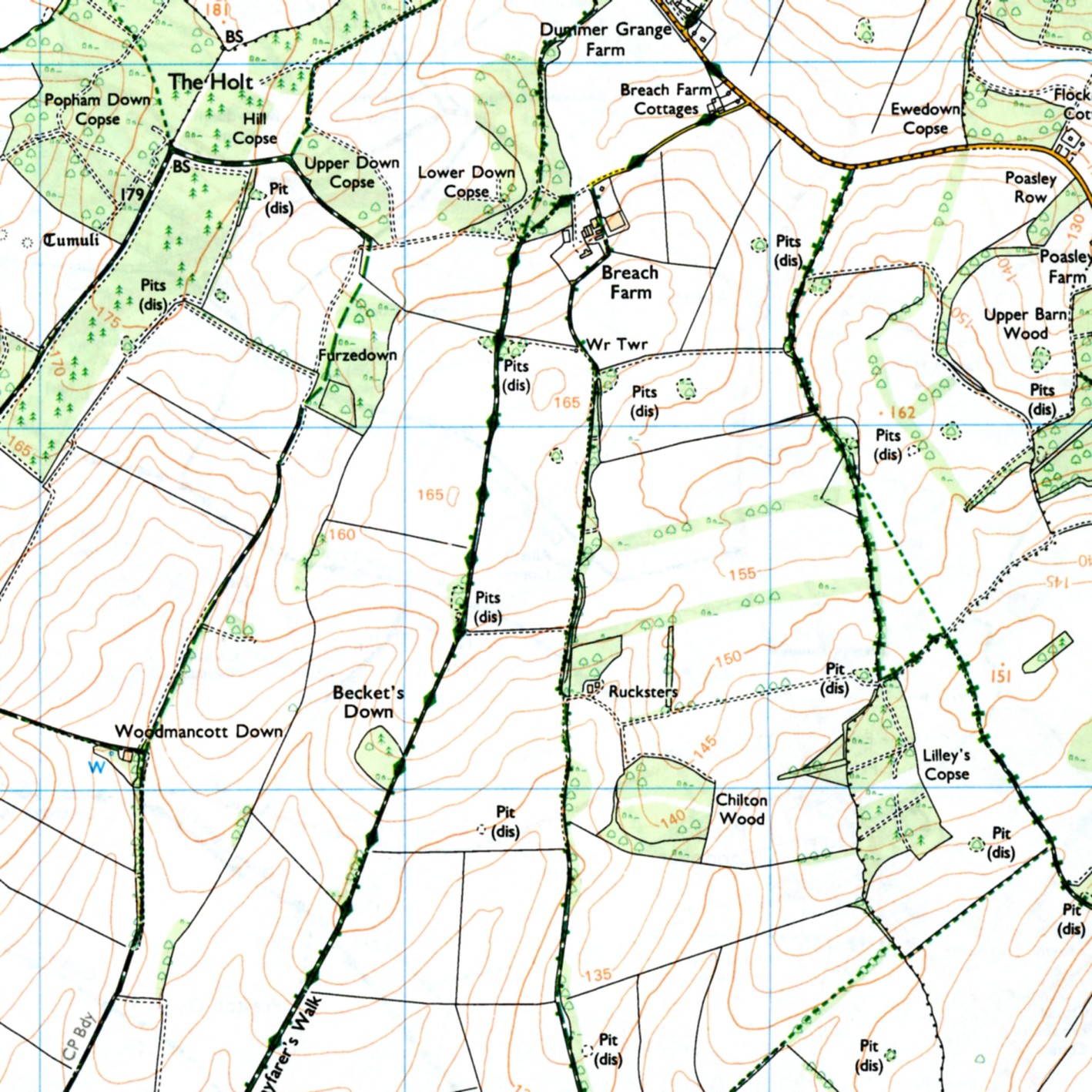

Of course, this is not the whole story. There is quiet – in between the gunfire from pheasant and partridge shooting, when their less appetising cousins can be heard. Coppices are festooned with plastic feeders and barrels that could grace a gallery space, as Duchamp-esque ready-mades, such is their utilitarian sculpted form. The only way to negotiate these places, without straying across the sight lines of twin barrels, is with the help of a map. Maps help keep us safe.

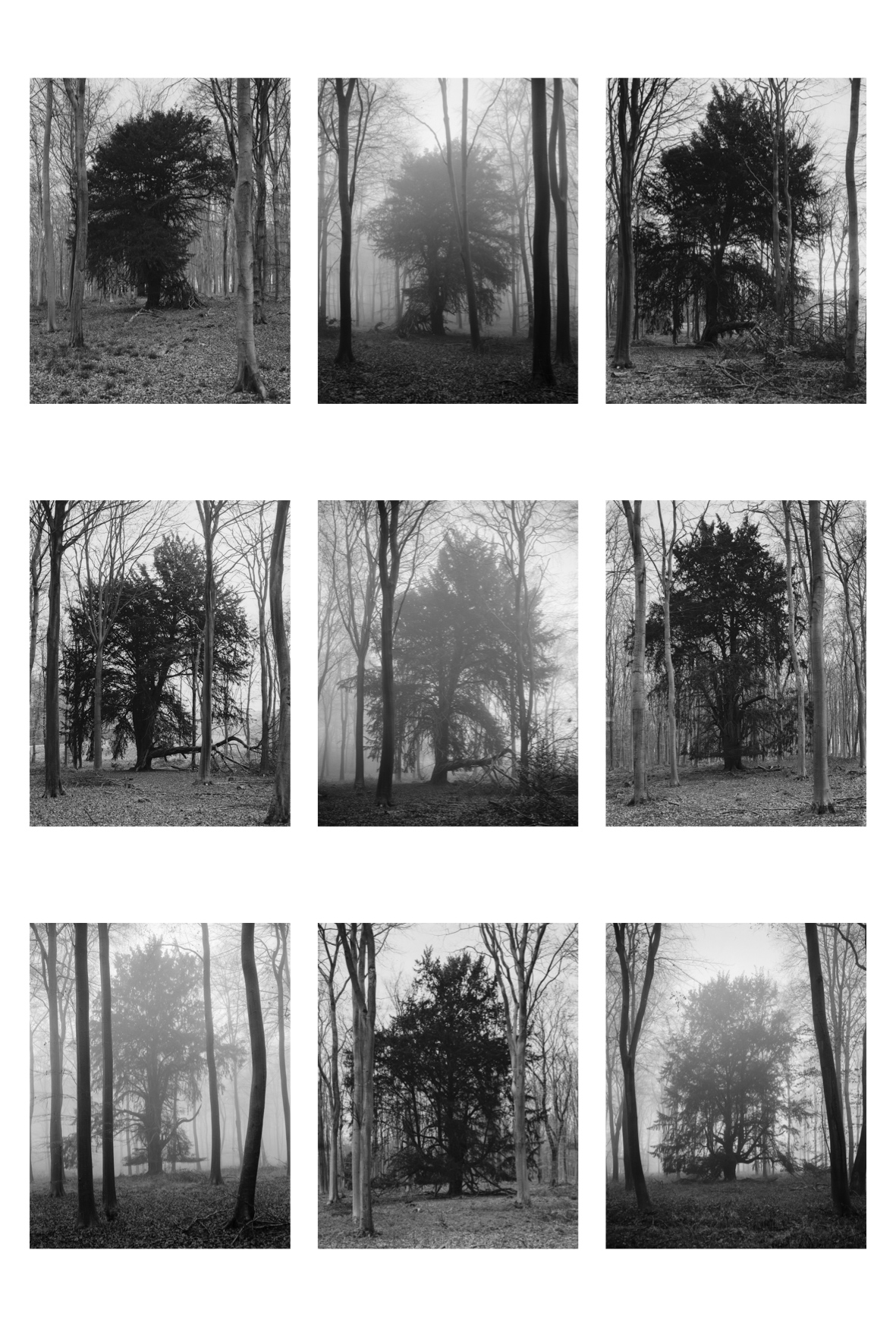

Untitled #1 ©djnorwood 2016

Maps also spur our curiosity, if we let them. At the risk of stating the obvious, the ordnance survey map aims to graphically represent three dimensional reality on a two dimensional plane, with all the necessary information needed for safe passage in the outdoors – the location of the nearest pub, for example, being of particular significance. But it also harbours information about physical features deemed necessary for safe passage through space. Pits are a fine example. Each one is marked as if it were a key feature to notice or negotiate – the map yielding these features – pit (dis) – as if they were waypoints on a quest. Yet in reality they are hard to find and usually disguised by mature trees, making full use of the fertile soil beneath.

An open chalk pit ©djnorwood 2016

We are aware of the significance of local actions on the global whole, and this is the starting point for my curiosity. This was reinforced recently by reading the fascinating and far reaching biography of Alexander von Humboldt, ‘The Invention of Nature’ by Andrea Wulf. Humboldt recognised the connectedness of the natural world back in the early part of the 19th century, and although much has changed in the way that we interconnect with each other, our interdependence with the land remains the same. Humboldt recognised both the significance of humans impact on ecosystems and the details of flora and fauna that gave flesh to his ideas. In the absence of so little of each, were he alive today, I’m convinced he would have searched out clues such as these.

Humboldt in South America: Versuch über die gereizte Muskel-und Nervenfaser (1797)

These particular ones aren’t heroic monuments like the usual totems of our recent industrial past – in Cornwall for example – where the chimneystacks of abandoned tin mines break the horizon like spires. These are intimate , hidden depressions, surrounded by trees, and this is the M3 corridor of rural Hampshire – a heavily industrialized zone of mono-cultural farms and fields.

A disused chalk pit, ©djnorwood 2016

Perhaps lingering significance lies with the map makers themselves, who have carefully documented their pock marked presence, laying cartographical bread-crumbs on the surface of paper, and leaving it up to the curious minded to discover and create their own narrative. Perhaps it lies in the simple notion that something insignificant marked on a map can arouse interest and curiosity, and this in itself should be a cause for hope and optimism.

Anyone with a (healthy) map obsession can scratch the itch at the British Library. The fascinating Maps and the 20th Century: Drawing the Line is open until 1st March 2017.